Opinions vary on how to run an RPG, to say the least. There are plenty of books, sites, and other resources already available and chock full of great advice. This chapter mostly provides specific guidance for running your dream game in METTLE Core. All of it is the author’s opinion; you already know you can take it or leave it.

Table of Contents

Settings

One of the first things to do is decide what world your group is set to explore. The heyday of proper “pulp” magazines was in the era of the 1890s to 1950s or so, but how can anyone truly limit the spirit of this larger than life genre? There are however a few sweet spots in the timeline for these wild stories:

- Wild West (~1860-1890): rough and ready cowboys, lawmen, and outlaws fighting to survive in a pitiless land. Play up the theme of law versus chaos. Often mixed with supernatural, horror or “steampunk” elements, to taste. Examples: The Lone Ranger, Zorro, Fistful of Dollars, The Wild Wild West.

- Lost World (~1880-1910): gentleman explorers or soldiers of fortune exploring uncharted and fantastic lands. Play up the contrast between the familiar old world and the fantastic new one. Examples: King Solomon’s Mines, The Lost World, Tarzan of the Apes.

- Hyperborean (Fantasy earth): Primitive low tech or ancient settings with some swords and sorcery elements. Such heroes rely on their steel and grit instead of falling to the corruption of magical means. Examples: Conan, Kull the Conqueror, Kane

- Atomic Age (~1945-1960): secret agents and outlaw inventors. Play up the themes of post-war optimism and cold war paranoia. Examples: Johnny Quest, Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow, early James Bond.

- Techno Pulp (Modern day): the modern world dialed up to 11. Play up the themes of isolation and progress. While the stakes are as high as ever, plots reliant on a lack of information must now contend with phones and the internet. Examples: later James Bond, Uncharted, John Wick

- Interwar (~1920-1940): the golden age of pulp adventure, around 1920-1940. The world reels from the effects of the great depression, the shadow of war, and rapid technological advancement. Often centered on the new ease of world travel. Examples: Indiana Jones, The Mummy, Doc Savage, The Rocketeer, The Gold Monkey

Further details can be worked out by the Guide and/or the table, ideally in a collaborative world building session.

A note of caution is that these media hold a lot of antiquated, racist, and generally ugly assumptions, some more than others. Of course this does not mean you cannot enjoy them, rather that you should be prepared to thoughtfully explore and examine their more “problematic” elements as they emerge.

Adventures

Naturally, a Guide running METTLE Core wants a game both they and their players enjoy. A story they feel like a part of. A world where their actions matter. For this to happen, view the game itself as creating an opportunity for a great story to arise, rather than telling one outright.

A good Guide keeps their ego in Check and loosens their grip on the plot. They become fans of the Player Characters, bringing out their inner conflicts and extolling their virtues. Given the freedom of a role-playing game, your players will rarely do what you want them to. Indulge them, and as they say, roll with it.

Session Zero

It is useful to hold one short session before starting to make characters and ensure everyone is on board. Reveal what the game is about, how often you play, any house rules, and how you handle missing players. Ask them to respect your veto power to limit arguments and help keep the game fun for everyone. Ask them what they want to see and do, and what they do not. Listen to them.

A thorough way to cover all the bases is to use the Five W’s: Who, What, Where, When, and Why.

- Who are the characters? International spies? An urban rescue unit? A mystery-solving knitting circle? Suggest FOCUS Attributes to help them make characters who fit the idea.

- What is the game about? Solve a mystery or crime case? Track down a spy? Deliver a precious package? Give them the starting plot.

- Where do the events occur? Baltimore? Bangladesh? A small town in Canada? This puts later events in context and makes it easy to add local flavor.

- When are the events taking place? Modern-day? The 80’s? the Roaring 20’s? The dark ages? This makes it clear what resources are available and what state the world is in.

- Why are they involved? Are they banding together in times of danger? Offered a prize? Embroiled in a mystery? This helps them come up with motives related to the situation.

Many of the old Pulp adventure stories that inspired the genre have just god-awful notions on topics like race and sex. Thankfully, Safety Tools help to avoid unfun or traumatic subjects. These are rapidly evolving, so search for the best current technique for your group.

If there is time left, start up a short introduction scenario!

Ongoing Sessions

Here your group explores and changes the setting. Do not fret over telling a story, following a plot, or even explaining things. Let everyone, including you, find out what happens next! The party may even diverge so much from the starting scenario that it becomes an entirely different game. This is fine. If you feel like the situation lacks something, try throwing in elements of Danger, Mystery, Obstacles, Consequences, Rivals, or Victories:

- Danger: planned or random encounters with doom can raise the stakes. It becomes possible to lose something precious, often their lives. Thugs, wild animals, lawyers, assassins, bureaucrats, repo men, etc. This is a common element, because it is great, but don’t overdo it.

- Mystery: adventurers face the unknown as a matter of course. A secret traitor, a shocking clue, a corpse in an empty room, levers in a secret lab, etc. Clues should reveal info and lead to a new Scene. This can even be a mystery to you - just riff on what they discover!

- Obstacles: hinder the party until they overcome a challenge. A sealed door, NPCs need a favor, mountains, the demands of fame, etc. Puzzles like these help with pacing and engagement with the world.

- Consequences: adventure is a moving target; the party’s world changes through their action and inaction. A villainous plan proceeds, towns rebuild, diseases spread, new powers come into being, etc. This gives the Guide the chance to let the setting breathe.

- Rivals: Great minds think alike – and the party has some competition! Rivals should be a credible threat to the party’s dignity, if not their lives. A Rival also gives the Guide a fun, scene-stealing character to play who is not just another enemy to defeat.

- Victories: Let the player enjoy their triumphs. You are their biggest fan after all. Their foes henchmen speak their names with dread, those they saved grant them favors, movements gain or lose momentum, etc. Resist the urge to erase their accomplishments just to drive home a feeling of gritty realism.

Be sure to keep an eye open to see which of these your group likes best but mix it up so they don’t get bored or complacent. You also don’t need to have all these things going on, especially at once.

Final Session

Through the chaos of the ongoing sessions, keep in mind how you could bring them to a close in a satisfying way. A showdown with the big bad, reconciliation with family, a great sacrifice, etc. This potential ending will probably change with every game but it does help you put the current events in perspective.

Ideas

When thinking up the rough idea of a game for your players, it never hurts to scope out adventure-themed books, games, and movies. Take inspiration from these and make them your own. Subvert them. Ignore them and do something different.

Some broad plot types to mine:

- Great Escape: Strand or imprison the party, who must find a means of escape. Rich ground for forming allegiances and solving puzzles. Examples: The Great Escape, Lost, Hogan’s Heroes, The Running man, Stalag 17, The Count of Monte Cristo, etc.

- Treasure Hunt: Make the party aware of a lost treasure, fugitive, or other irresistible macguffin that could change their lives. Heavy on travel scenes, traps, and rival parties. Examples: every Indiana Jones, The Goonies, The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly, Romancing the Stone, Tales of the Gold Monkey, etc.

- Countdown: The party learns of a scheme or ultimatum threatening what they hold dear. Usually followed by infiltrating the threat before directly confronting them. Examples: The Rock, Outbreak, A View to a Kill, Moonraker, Dr. Otto and the Riddle of the Gloom Beam, etc.

- Rescue Mission: The party finds out an important person or creature is missing or captured and sets out to retrieve them. This always has a cost, whether negotiated with self or others. Examples: Big Trouble in Little China, The Wicker Man, Saving Private Ryan,

- Special Delivery: The party must deliver an important message, item, or person. Guaranteed to be a stealth or chase scene somewhere. Examples: The Transporter, Pulp Fiction, Children of Men, From Russia with Love, Tears of the Sun, etc.

- Whodunit: Embroil the party in a mystery they must solve. These involve lots of Know Checks and player ingenuity, so make sure to drop enough clues to keep it moving. Examples: Chinatown, Live and Let Die, Clue, The Maltese Falcon, etc.

Consider that each of these needs a “hook” - a reason for the party to get involved. For example, a rival lets it slip, it is in all the news, a superior tells them to ignore it, it results in the death of an ally, as a loose end from a prior case, etc. If they don’t take the hook, change your bait or fish elsewhere.

As mentioned earlier, do not get attached to a plot. Maybe they use your setting as a sandbox, maybe as a litter box. Always remember, however, that you are a kind of player too. if it stops being fun for you, you can always stop running it for them.

Combat Tips

A well-founded complaint about RPG combat is that boiling the sheer mayhem of fighting into a die roll can get repetitive after a while. While rich narration helps, there actually is a lot more the Guide can do to keep things interesting. Each of the following methods create more opportunity to make interesting and meaningful choices:

- Variety: mix and match foes with different abilities and tactics; throw a big guy into the brawl with the regular bar scum, give the tank a motorcycle escort, reveal one cultist as a famous person, etc.

- Stages: unveil layers of foes or challenge as the fight escalates. The next Scene changes depending on the outcome. For example, a lengthy fight with one gang leads to their rivals showing up.

- Objectives: present foes as obstacles to a more pressing goal. For example, pressing through a mad scientist’s minions so they can shut off the doomsday device on the balcony.

- Spectacle: nothing suits an adventure putting on a show. Brawling atop a moving train, through the flooding corridors of a sinking ship, a monsoon, the treacherous steps of a ziggurat…

- Tactics: it is not just the players making interesting choices, two can play at that game. Attack from hiding, use distractions, hide your strengths, flee when outmatched.

- Zones: lay out Zones with special features to choose from like cover, elevation, difficult ground, etc.

These tricks and others should help keep your fights bold and memorable. Remember that for a combat to be interesting, there must be interesting things to do in it. As good as METTLE Core is, if you depend only upon the system, you will be dice-appointed!

Faction Tracker

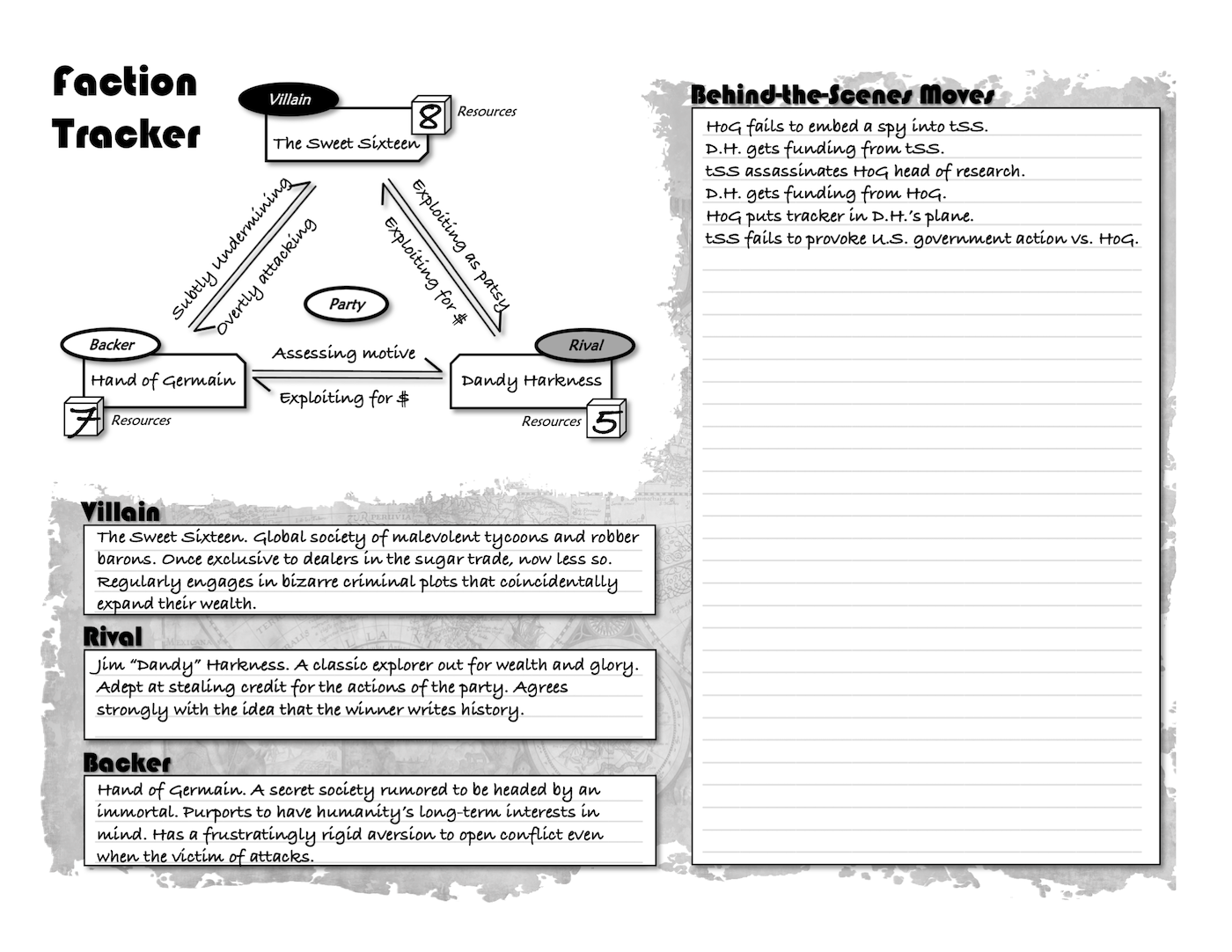

A web of conspiracy influences an adventure party behind the scenes. The faction tracker is an optional tool that helps the Guide keep track of three staple Factions in pulp adventures: the Villain, the Backer, and the Rival. If your setting is different, wing it or set your own web up on the Blank faction Tracker.

- Backer: a person or group that aids the party. They can be relied upon as a helpful contact or for aid behind the scenes.

- Rival: a person or group that competes with the party. Often another party with similar means but different methods.

- Villain: a person or group that opposes the party, and vice-versa. The main driver of conflict in the game.

FACTION SEEDS

| Roll | Enemy | Backer | Rival |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Zealous Cult | Secret Society | Fellow Adventurer |

| 2 | Sinister Genius | Government Agency | Unpredictable Weirdo |

| 3 | Ruthless Corporation | Wealthy Philanthropist | Sly Trickster |

| 4 | Shadow Conspiracy | Curious Scholars | Bumbling Oaf |

| 5 | Greedy Criminals | Religious Order | Vengeful Ex-member |

| 6 | Aspiring Overlord | Mysterious Voice | Suspicious Investigator |

Each Faction has a box for its name, a cube for its Resources, and arrows for its relationships. Roll 1d6+3 for each Faction, giving the Rival the lowest. Adjust if not satisfied – these change only from extremely impactful events. The sides of the triangle are bidirectional arrows – jot down their relation to each other, above and below.

Resources come into play when factions deal with each other. For example, the party’s Rival may try to finagle their Backer into lending him a helicopter originally meant for the party. The Rival Checks their Resources vs. a Difficulty of the Backers’ Resources. A Twist defaults to them dealing with the fallout from their plotting instead of taking part in the next Faction turn.

FACTION RELATIONS

| Roll | Relation | Elaboration |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Colluding | Working with them as collaborators, secret or open. |

| 2 | Extorting | Forcing them to do something or face dire consequences. |

| 3 | Undermining | Subtly deteriorating their power and reach. |

| 4 | Evading | Hiding, fleeing, defending, and evading conflict. |

| 5 | Attacking | Hostile and actively trying to destroy by whatever means. |

| 6 | Appeasing | Giving them what they want, to curry favor or halt attack. |

FACTION TRACKER

Powers

METTLE Core embraces weirdness but keeps a little distance from overt magic and super-science. These numinous mainstays of pulp fiction are often still present, but secret and special. If they appear, they tend to be plot elements: inventions of mad scientists, alien devices, or villainous sorcery. For example, a stolen idol that calls rain, a death ray, cultists summoning a loathsome entity from beyond, the holy grail, a gorilla with a human brain, etc.

You can run these as narrative trump cards that simply break or glitch reality, very fancy special equipment, or as full characters in their own right. If players get ahold of them, let them have their fun. In the long run, they can always run out of charges, have disastrous side effects, be confiscated by “top men,” etc. There are other games and settings made for those who regularly traffic with such forces.

Characters

An expected feature of this genre is the characters are always changing or evolving. Players may want to change their character’s Attributes, Backstory, etc. After the first game, you should even recommend this so they can make a character who works for them. In later games, ask for some justification but be lenient. No one should feel trapped by choices they made before becoming familiar with the rules, setting, or story.

Sometimes a new character comes along, or old ones die or retire. A new character should start with an Attribute pool total (highest x 2 + all lesser pools) equal to the lowest in the group. Discuss how to work them in; ideally by linking them to the current situation. A surviving villain makes a great replacement character and saves time on introductions. This is also true of their henchmen or any other interesting NPCs the party hasn’t entirely alienated or deceased yet.

While it is always best to have everyone at each game, things happen. Missing players can still get XP by recalling their highlights from the last session they attended. They can also get a bonus “make-up” XP for each missing session by explaining what brought them back into the story.

NPC Creation

The Guide plays perhaps too many NPCs, such as friendly or unfriendly contacts, shopkeepers, enemies, key figures in the setting, and random passersby. Only key NPCs have full Attributes. For the mostly unnamed, unsung Extras, a single NPC pool will do. The first number, followed by a “D,” is their dice pool for combat Attributes as well as their Mettle. This is followed by their FRAME bonus. Think “Stunned Bystander 3D+3” or “Hostile Village Elder 4D+2.” Raise the pool by two for Checks strongly related to their title, as if it were a CALLING.

As their NPC pool gives them less Mettle than regular characters, they have less staying power in a fight. Embrace this as meeting their doom easier or play it up as a retreat.

What Do You Know?

METTLE Core gives example CALLINGS but does not limit players to a definitive list of skills. The table decides if a given CALLING is relevant to a task. Most of the time, the answer should be yes. If not, default to another Attribute (Motive, Nature, or Poise) and consider their Background for context. It may seem backwards, but one is only unskilled at something if their player says they are – and all this does is downgrade what they are Checking for. For example, someone who can’t speak French can use a Know Check to spit out a few words.

Flaws

Some players may want to limit or disadvantage their character in some way, such as nearsightedness, a missing arm, or an addiction. They are free to do so and should find a way to work it into their attributes, appearance, and background. The Guide should do their best to alter the situation or Check to bring it into play. Of those players, a subset will ask for more attribute points or other advantages to “make up for it”. Do not give them these. An interesting flaw is its own reward.

Weapon Guys

In more combat oriented games, the first instinct is to “build” a character around a weapon to make them more efficient. While not encouraged due to being a bit one-note, it is easy to do in METTLE Core by including the weapon name in their CALLING. For example, a Marine Sniper or Mercenary Swordsman. This lets them use the implied weapon or group of similar ones at their full CALLING as usual.

Freeform XP

This method can be freeing for many groups but confusing for others. Players are meant to choose for themselves what they felt was XP-worthy about the last game and provide a useful recap while they are at it. If you feel the urge to reward a player with XP, consider doing this more directly by changing the way the scene plays out instead.

Some consider this method controversial. If you are one of them and this freeform XP does not work for you, patch in a more traditional set of rewards from other games. keep them within the same range of 1-3 XP per session and there should be little trouble.